In his excellent book The Moor, William Atkins equates moorland with the sea. Moorland can seem equally featureless and appear to shift colour, appearing brown, red, black or green as the light and perspective change. But just as when you sink a glass into the sea and hold it up to the light it's always clear, look to your feet and you see the usual mix of heather, grasses and peaty brown.

Moorland presents unique challenges to the navigator. During a recent Pure Outdoor Intermediate Navigation course, the candidates successfully navigated to the 'summit' of Kinder Scout, an innocuous spot height at 636m. Visibility was fair, about 200m, and all were chuffed to have nailed a challenging leg. Cameras came out and snacks were had, but soon enough the chill set in and thoughts turned to getting moving.

"It's back that way," said one, pointing in to the cloud.

"No, we came from that way...didn't we?" replied another.

The featurelessness had disorientated us completely in the space of ten minutes, without compasses we'd have floundered.

The Kinder Scout plateau covers approximately 12 square kilometres with only 40 metres of vertical range. The mountain owes its distinct shape to its geology: The tough Kinder Scout Grit sits like a table top over thin layers of shale and mudstones which erode readily creating Kinder's steep flanks and deeply incised gorges. This sequence is typical of moorland areas of the Pennines and Brecon Beacons, steep approaches give way to high, plateaued areas covered in peat.

The presence of peat reveals much about the prevailing climate and terrain. For peat to form, atmospheric conditions must be such that the rate of plant decomposition is slower than the rate of new growth. The low average temperatures and soil acidity, associated with high rainfall, combine to slow the decomposition of dead plant material. New growth continues atop a growing pile of undecayed material forming a peat 'hag'. The hags are islandised by downcutting of water channels, known locally as groughs, which can be several metres deep and challenging to negotiate.

On average, rainfall exceeds 1mm on a minimum of 10 days per month. So, to traverse Kinder Scout, or any moorland terrain, in comfort then you must work with the landscape.

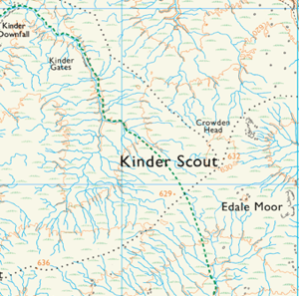

Let's start by rethinking how we see water on the map. Instead of a messy tangle of blue lines...

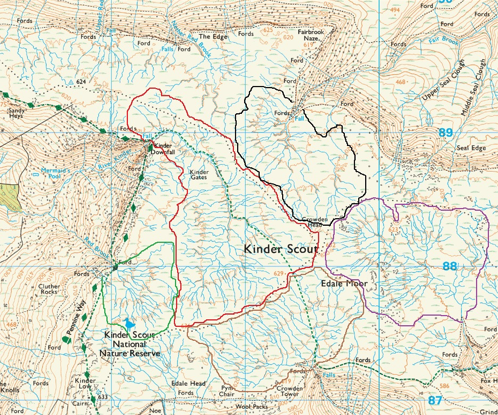

...think more in terms of the overall hydrology of the plateau - watersheds, catchment areas and main drainage channels:

Shown this way the moor is more akin to a transport network; a patchwork of concave landforms funnelling towards a main outflow at the edge of the plateau, bordered by watersheds affording relatively dry, easy walking. Navigation becomes more harmonious with the landscape and less about fighting your way up hag and down grough. The outflow of Fairbrook may be small, but it's catchment covers a square kilometre.

Water courses shown as single blue lines on the OS Explorer 1:25,000 maps can be up to 6.25m across, so proceed with caution, particularly in wet weather. It's also useful to be aware of Ordnance Survey's rules regarding where water courses are shown to begin. Common sense tells us that streams don't just begin. Water gathers in depressions (catchments) from which channels flow downhill. Only once a channel has cut through the superficial layers / top soil and bedrock is visible is the water course shown with a blue line.

Between the water courses on moorland, heath and grassland (sometimes called bents) predominate. Mat Grass, Bent and Fescue; Bilberry, Cloudberry and Heather are the dominant species. Tough, tolerant of the harsh conditions and all useful indicators of dry ground.

Finally, no piece on moorland navigation can overlook the infamous bogs, claimers of many a walker's boots. Indicator species include Soft Rush, Cotton Grass and Purple Moor Grass, steer clear, especially if water is visible on the surface.

The ground can sometimes ripple underfoot, like you've stepped on to a water bed. Sphagnum Mosses are common on damp moorlands and whether living or dead can retain up to 26 times their dry weight in water, creating a wet 'mattress' of bog that remains in-situ even on inclines.

Expert Tips:

Use the watercourses as handrails connecting the watershed to the outflow.

Use the watersheds to traverse the plateau and to access other drainage systems.

Avoid crossing water courses, go with the flow.

Consider water levels and know how to identify waterlogged and dry terrain.

Always carry a compass.

No comments:

Post a Comment